|

Kyle may run the farm, but he is not in control. The weather is. "It's kind of amazing to me how many decisions I make based on what the weather is doing," he says. Essentially from the time that the ground thaws in the spring to when it freezes in the winter, Kyle has his eyes on the forecast. He's watching for the fieldwork, of course, but weather also influences our weddings/events, our berry season, and our fall season. What Kyle looks for varies from week-to-week but also from type of work-to-type of work! In the springtime, Kyle is immediately looking for when the snow will melt and when the frost will come out of the ground. A lot of his work is driven by how wet the ground is. When we have springtime weddings, he looks at how wet the ground is to make sure we don't leave ruts when bringing our ceremony benches out of storage. This often means comes in very early in the morning - when the ground is still frozen - to transport the benches without tearing up the lawn. Mowing is also another farm activity that is driven by the weather - the wetness of the ground drives when and where we can mow. Sometimes Kyle or one of our staff can mow all day - other times it's just for a couple hours in the afternoon after working on other projects waiting for things to dry out. The fieldwork, however, is the most pressing and the most weather-dependent. Strawberries are the first thing on the springtime list, and we usually plant sometime in April. Because we get small berry plants from a company in Massachusetts, Kyle pays close attention to the weekly forecast so he can get the berries shipped to him within the right window. If it's going to rain, he'll hold off on delivery for another week or so to keep the berry plants in cold storage as long as possible. This year, he went through a shipping issue week after week after week because of all the wet weather. There ended up being no good time to ship the berries, so they ended up in our cooler for about three weeks before we were able to get enough dry weather to get them into the ground. It wasn't the best for the berries, but the sheer determination of the rain necessitated this unique situation. Unfortunately, this was a theme for berries this year: the continual wet weather and absence of heat made it difficult for the berries to ripen evenly, and we experienced problems over and over with our berries because the weather simply didn't do what the berries needed it to do. In the spring, we also plant pumpkins, which are not nearly as bad because they are seeds (not small plants) and they are generally planted later in the season, in late May. This year, however, it was still delayed because of the wet weather, and we didn't get them in the ground until mid-June. In fact, our business/marketing intern spent her first day on the job planting pumpkins because it was go-time and we needed an extra hand - not something she expected when she signed up for this internship! Speaking of farm hands, weather even influences how many people Kyle has around to help him out! Most of our employees are in school or work another full-time job, so may of them aren't able ability come in on short notice on a weekday. When it's crunch time to get berries or pumpkins in the ground, Kyle can spend a few hours on the phone trying to find a few people to fill in round-the-clock shifts to get things planted. A lot of times when planting is in full swing, both the weather and our employee's schedules can mean some really wonky days for Kyle and the gang. Early mornings to get paperwork or scheduling done; then off for a full day of fieldwork; and then at night, a few hours of working in other things, like necessary projects (we had a few very late nights during our bridal suite construction) or setting up the barn for an upcoming event. Once we're fully into summer and berry season is over, Kyle watches the weather to ensure things are done in time for our weddings and events, but also for windows of time to get projects done around the farm. Rain can often delay work on buildings, building new activities, or setting up for outdoor events. Summer is the time that Kyle can prioritize these projects, but if the weather doesn't hold up, they can be significantly delayed or canceled. Oftentimes, it's a matter of fitting these things in around the other daily things that need to be completed...when the weather allows, which again, can mean an abrupt change in Kyle's whole plan for the day based on what the weather throws at him. During our fall season, Kyle's attention to the weather drives how many supplies he orders week-to-week, how he schedules our staff to cover the shifts, and how he plans picking pumpkins from the field for our retail area. He's constantly asking questions like, "Is the weather going to be hot so I might need more water? Or cooler and nice so I need more cups for hot chocolate? Will the weather exclude many people from coming to the farm so I need a smaller staff?" Every day is a question of what the weather will do and how will it affect fall season attendance and therefore affect Kyle's daily decisions. Finally, when we close for fall and head into winter, Kyle scrambles to not only keep up with our private events and weddings, but also to get the fall tillage done, work on the berries, and take down and store all the things we use during fall season before winter fully hits and the ground freezes over. He needs a good few weeks of okay weather to get these things done, but last year, winter did not allow that. It froze over so quickly that some things were left out and a lot of the maintenance on the strawberries didn't get done. These things were left undone because of the weather, which can mean problems for the berries in the coming year and, of course, more work in the spring. From April to November, Kyle's days are fully driven by weather. It affects his fieldwork, his scheduling, his meetings with people for the business end of his farm, and how many people are able to enjoy the things our farm has to offer. Over and over, Kyle asks himself "What is the weather going to allow me to do?" The answer to that question affects not only his day, but his employees, and his guests, so the answer is important for so many reasons and therefore one of the most significant - and stressful - things he does here on the farm.

1 Comment

This past weekend, I brought my little assistant to help transplant Bruce's giant pumpkins. Okay, he didn't help at all (these pumpkins need a practiced gardener, not a 2-year-old on a mission to move all the dirt in Grant County), but we did get to see the next step in giant pumpkins: getting them into the ground! Last week, Bruce planted six giant pumpkins, and Saturday he put two more in the ground. We helped with one. He trimmed up these baby bigs, removing flowers and extra leaves to get them ready for planting. Then we drove over to the field, which might not look like an action-packed place right now, but the real magic is about to start. Bruce plants these pumpkins sideways so they can follow the ground and so they don't break under their own weight as they grow. He spreads some Miracle Grow, kelp fertilizer, and a little insecticide for each plant to give it a bit of a boost, then he diligently gardens it for the next couple of months.

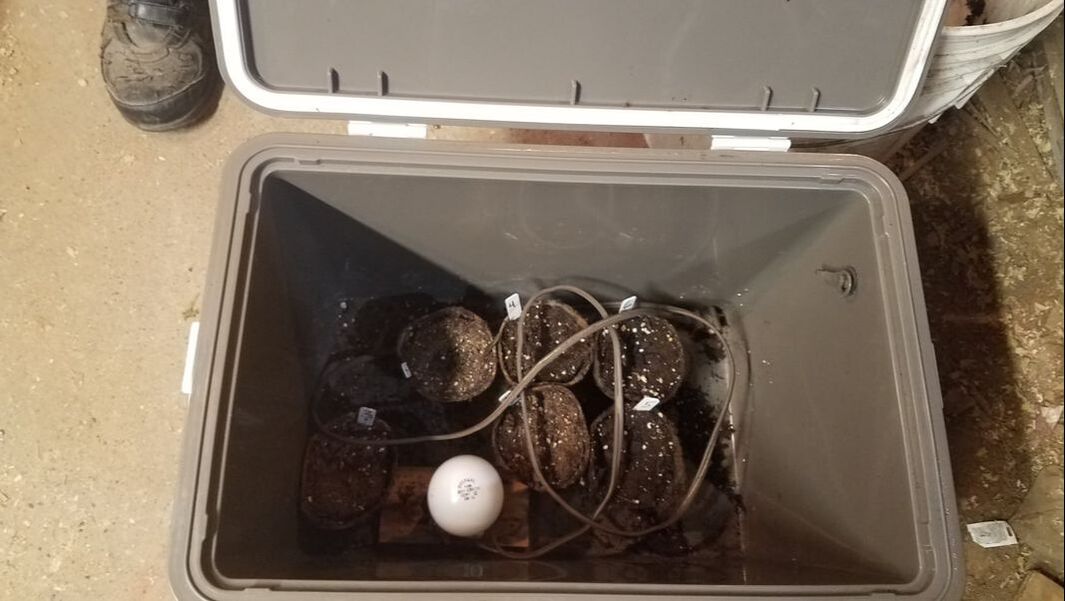

Each plant is planted about 20 feet away from each other to give them enough room to grow. The goal is to get them big enough and strong enough to have a pollinated pumpkin by the 4th of July, which means that soon this empty-looking field will be a sea a green leaves. These pumpkins can grow up to three feet in just a day, and Bruce says that to accomplish that amount of growth, they need the right amount of rain, good heat, and a lot of love. When I asked him how long he will spend with these plants in the next few months, he laughed and said: "You don't want to know." (Kyle added that Bruce spends more time with these eight giant pumpkins than he does with his 8-acres of normal-sized pumpkins!) My little gardener and I will be checking back in on these pumpkins in the next two weeks and we can't wait to see these plants grow! Last week, I visited Bruce in his giant pumpkin nursery and learned a whole bunch of things about turning these big ol' seeds into big ol' pumpkins! Bruce gets his seeds from the Giant Pumpkin Growers Association, and he spends quite a few weeks marinating them in some special growing sauce and planting them into small starter pots. They spend a few days in Bruce's makeshift incubator, which is a small cooler rigged up with a lightbulb and kept at a certain temperature. When - and if - they germinate, these baby giants are moved from the cooler to a little bigger space: the back of Bruce's shop. There they stay safe from the cold temperatures under a heat lamp, and get the start they need to grow. The plants are all labeled (genetics in big pumpkin growing is a BIG deal - pun intended) and kept sorted until they are turned out to the field. This year, Bruce has about 10 pumpkins that have started to grow and each one has the potential to be a giant - one plant has grown from a seed that was harvested from a pumpkin that grew to over 1,000 pounds in size! In the next week (if it ever stops raining!), Bruce will be transplanting these future giant pumpkins. I'll be following along the whole process, so stay tuned to see how these babies grow and grow and grow!

Ever wonder how strawberries grow? I did, so I asked Kyle. And he dropped a lot of berry knowledge on me. We don't start our strawberries from seeds, but as plants: a little tiny crown, which is the growing part of the berry, and a root. We purchase this rootstock from a nursery in Massachusetts that specifically raises these little plants and sells them to farms. Kyle picked this nursery in particular because their climate and growing region is similar to Wisconsin's, which makes it easier for plants to adjust and flourish. Sometime in mid-April, Kyle watches the forecast for a few days of good weather and then places an order from the nursery. They then take 15,000-20,000 small strawberry plants out of cold storage, package them up into bundles of 25, and ship them overnight on FedEx Freight to the farm. Once we get them, the real work begins for us, because in the next 2-3 days, all those little plants go in the ground. Kyle, his family, and our fantastic employees work shifts sunup to sundown to plant these little guys, working on a machine called the Transplanter, which can plant up to 1,000 plants per hour. If you want to check out how we plant these berries, check out our Behind the Berries blog! For the first year, we don't interfere much with these little plants. They need this year to grow on their own. All during this time, these individual plants send out runner plants (called "daughter plants"), helping the plant grow and multiply and turning all these individual plants into multiple connected networks of vines. Oftentimes, the plants do fruit (grow berries) during this time, but we come through and pinch these berries off. We want the plant to put all its energy into growing and multiplying so it has a good base for fruiting in its second year.

During the first part of this growing year (in the fall), we do need to care for them. They need weed control and we go through and mechanically cultivate and till the soil. The runners like to go pretty wild, and they don't grow naturally into the neat rows we enjoy while picking berries. Therefore, we have to stop their expansion into places we don't want them to grow in by tilling the plants that are in those areas under and encouraging other runners to grow in rows. A lot of the maintenance that we do during that first year is to make things easier for the pickers - neat rows make it easy to get in an out of fields and give people more access to the berries that they love. Over the winter, the plants will go dormant. After we've tilled, we spray a pre-emergent on the plants and cover them with straw. Although this is to protect them from the cold, it's mainly to help with the springtime growth. As soon as the sun comes out, the berries wake up and want to grow. The straw delays their growth, but in a good way: it slows down their "awakening" so they don't grow too soon or too quickly. The straw also helps suppress weeds and fills the gap between the fruit and the bare ground, therefore protecting the berries from fungal infections that come from the ground. We watch the plants closely throughout the spring and into the summer, and if all goes well, in June we have a great picking season! Once the picking is over, we mow everything off the top, fertilize the field, and do our best to control weeds. Even though there isn't anything aboveground after we mow, the root structure of the plant is still intact below, so the berries spend the rest of the summer and fall establishing new daughter plants and crowns for good fruit. Then we just repeat our process for the next 3-4 years until it's time to rotate fields, which you can read about here. In the next couple of months, we'll feature more of our crops, including raspberries, pumpkins, and our giant pumpkins. Stay tuned! If we're going to start to answer the question How We Farm, I think we need to understand what exactly is our farm. Not the history, but the parameters.

The whole farm is 200 acres. The part everyone is used to and knows about is about 40 of those acres. On those 40 acres are the activities area, the main barn, parking lot, berry and pumpkin patches, and corn maze. The rest of the farm that you see but don't play on is field ground for alfalfa, corn, and soybeans, or whatever the farmer who is renting the land decides to plant that year. The 40-acre difference is made up on a parcel of ground that the family owns just down the road. This is hilly land, with a stream running through it, that is primarily used to grow corn and silage. This gets cut into a salad that feeds dairy cattle at a local farm. Those are the straightforward stats of the farm, but if you want to learn all about the farm's history and past, check out our blog Celebrating 118 Years of Vesperman Family History! While I was out riding in the pumpkin wagon this past fall, a few people asked me why our pumpkin patch had moved. I sort of fumbled an answer about what I assumed was crop rotation, but I realized I really didn't know. And when I don't know things, I bother Kyle. So I asked him: Why do our pumpkin patches move? Crop rotation in a nutshell can accomplish four major things. First, it improves soil nutrition. Crops take a lot of nutrients out of the soil, but they also put some back in. And each crop will take and put different kinds and levels of nutrients out and in of the soil. Moving the crops around can replenish nutrients in the soil, give the land a break from certain crops that can very quickly deplete essential soil nutrition. Rotation also helps keep soil erosion under control, which also helps keep the land healthy and able to continue supporting crops. Second, it help slow down bug and insect infestation. Rotating the crops keeps bugs confused - what was once their preferred food has now moved - and therefore they don't find the crop as quickly or infest as rapidly if you keep them off their game. It can also disrupt the reproductive cycle of breeding insects, meaning that they struggle to either lay their eggs properly or newly hatched insects awake to a different or unacceptable food source. Third, it helps fight agains fungus and virus in plants. Much in the same way that rotation fights insect infestations, it can ward off fungus and virus, too. When fungus finds a plant and a virus inhabits an area, continuing to plant the same crop will encourage the growth of these problems, while switching the crops can slow or even stop their progress through a plant community. And, finally, it helps to control weeds. Rotation makes for healthier crops that will out-compete infestations of weeds and other invasive plant growth. It can also disrupt weed growth that will occur more frequently and rapidly in a mono-culture, which is a long-term growth of the same plant in the same area. Basically, how I understand it, is that moving the crops keeps the problems that plague and pest both crop and farmer guessing and off their toes, which means the crops have a much better chance of survival and the farmer a better chance of a successful crop. Now that I understood the basic premise, I had a few other questions: Why do the pumpkins move every year and the strawberries stay in one place for a couple years? The short answer is they have different growth cycles. The long answer is the berries are a perennial crop and the pumpkins are an annual crop. Annual crops start from a seed, grow, mature, multiple, and die all in one growing season. Perennials like strawberries start and grow in one year, multiple and reproduce in the second year, and continue reproducing and maturing in the years following. For annual crops, moving them around is essential and logical: they are restarted every year and so they are able to be moved frequently. Production of strawberries drops off after 3-4 years of keeping them in the same spot - after this time, the nutrients in the soil have dissipated and bugs and fungus have often found the plants. This means it's time to give the field a break and move the berries to another location. Does rotation cut down on the use of fungicides and herbicides? Yes, it can. But so much of this also depends on other growing factors, like the condition of the soil, the weather patterns, and the health of the seeds and young plants, so rotation doesn't always guarantee that these aren't necessary for a healthy crop. Do farmers have to plan out their crop rotations years in advance? Depending on the size of the crop land and the number of plants in rotation, yes. Smaller farms can often undertake less planning, but more the more you have to consider, the more complicated the rotation plans get. Ours are pretty simple, so we plan a couple years out. For more blogs about how and why we farm, check out our How We Farm tag. And if you have any questions, drop them in the comments!

A lot of things we need to live, plants need, too. Many times, we are asked if we use fertilizer and chemicals on our crops, and why we use them. To start off our new series of blogs about How We Farm, we're going to address what always seems to be the elephant in the room: Why do farmers use chemicals on the food we eat? FERTILIZER USE We use fertilizer on our plants, including our pumpkins, strawberries, and raspberries. There is no danger in using fertilizer for plants. In fact, fertilizer provides to the plant some of the essential nutrients they need to grow (and many of those things are essential to our nutrition as well): Potassium, which we get from bananas (the most popular and well-known source); phosphorus, which is found in a lot of the green vegetables we try to get our kids to eat; and nitrogen, which we actually breath in from the air. What's often misunderstood is the delivery of these fertilizers. Nitrogen for example, can be a gas, liquid, and, in fertilizer form, a solid. Smarter people than us have found a way to attach nitrogen to other molecules to make it solid in a pellet form, which is how it - and other nutrients - are sometimes delivered into the soil to fertilize the plants. It can seem weird to some that these essential nutrients, found so naturally in our food, can be formed into what seems an unnatural form. But it's just a modified form of delivery that uses the different state of the matter plants need. It's basically the same concept as multivitamin - but for plants! PESTICIDES, FUNGICIDES and INSECTICIDES (referred to broadly as "chemicals") It's not necessarily that we like using these on our crops, but it's really just that we HAVE to. If we didn't more years than not we would have a crop failure. Even though many people struggle with the idea that we use chemicals on our food, the pesticides and fungicides that we use on our crops do keep our plants healthy and alive. For example, some years strawberries can end up with a bitter taste. This is the result of a fungus. Most fungi start from spores that are naturally occurring in the soil and they get into the plants through water. Rainwater is a great conduit for fungus. The splash of water on the ground will deposit spores onto the plant. Usually once a fungus gets on a plant and takes hold, it's "game over" for the plant. The best and most effective way for us to keep fungi at bay is to use a fungicide. At the farm we use an antibacterial/anti-fungal spray on our all crops (differing slightly based on the crop we're spraying), which is similar to us washing our hands with antibacterial soap. We don't want germs on our plants any more than we want them on our hands! Pesticides are used at the farms, too. These are used mainly as a deterrent, but not a killer, of bugs. Bugs find and inhabit plants and can be seriously damaging. One way we combat bugs is crop rotation (we have a blog coming up on this soon!), but the other way is using pesticides. If you use Off! or Deet in the summer to ward off those insects, you're embracing a similar concept to what we're trying to do with bugs on plants. We don't necessarily want 'em dead, we just don't want 'em on our plants. Many people see pesticides and fungicides as bad or poisonous, and we will concede that they are not our favorite things to use on our plants. However, to provide some context, bleach and many of the other household cleaners you can find in the cabinet under the sink pack a bigger punch that the chemicals we put on our plants. We know you like sweet-tasting berries and plump orange pumpkins, so we do what we can to keep these plants healthy and happy so you can be healthy and happy, too.

If you have any questions, feel free to drop them in the comments - we'll be happy to answer them the best we can! |

Vesperman FarmsFun on the farm...in blog form! Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed